I could write a book about Roger Skime, detailing his gigantic impact on the sport of snowmobiling and his even greater role at Arctic Cat.

But what I’m more impressed with than his inventiveness is the absolute dignity and respect that he brings to the sport.

Whenver there has been a major snowmobile race over the past five decades, Roger has probably been there.

THE most passionate competitor in a company chock-full of them, Roger embraced racing when he came to the company in 1962 and never once let go.

If you’ve ever wondered why Arctic Cat has been an over-achiever in racing, the answer starts with him.

Roger himself has always been a racer, especially in the early years of the sport and company.

In recent decades, Skime would occasionally defy company expectations that he “hang up his race helmet,” and put himself back into the competitive arena.

Case in point: During the 1999 race season, engine gremlins plagued the ZR Sno Pro race sled, and the Race Department was struggling to find a fix. On the eve of the I-500 (above) and still unable to diagnose the problem, Roger literally entered the race at the last possible minute. He had to borrow a sled, helmet and other gear to pull it off, but that’s exactly what he did.

For the past four decades, though, Roger has typically been a spectator.

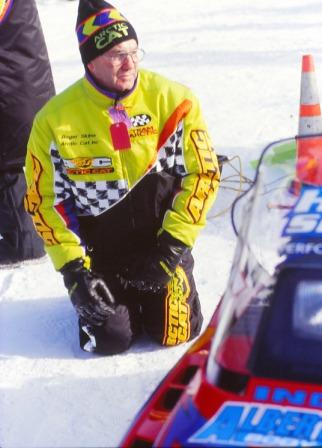

And at each race, he spends a considerable amount of time studying the competition, like he’s doing here at an ISOC cross-country race in 1996.

For the man who invented the slide rail suspension, I’m always struck by his utter lack of ego. If he has an ego, I’ve never seen it.

Nope, his personal pride has never prevented him from getting on his hands and knees to study a competitor’s skidframe, or to humbly acknowledge when another company has developed a better technology.

To see Roger’s face when one of “his” racers wins is to see a joy whose depth and passion have no end.

One time I saw tears of despair in his eyes. It was at the 1998 Warroad I-500.

Going into the third and final day, Team Arctic’s Trevor John had the lowest time, a solid sled and a lead that seemed insurmountable. Battling flat light and the unimaginable nerves that accompany a young racer in that situation, John missed a course marker just a few miles from the finish, racing for several minutes in the wrong direction before realizing his mistake.

Panicked, he turned around and raced back to the course, but by then it was too late. He’d been passed by Todd Wolff.

It was a crushing blow to John. After crossing the finish line, he simply hung his head and wept. And Roger wept with him. Not because Team Arctic lost, but because of the deep empathy he felt for John.

What illustrates Roger’s greatness best that day, happened just moments before he shared a tear with John.

In the competitive arena of snowmobile racing, passions run deep and strong. To those who pit themselves against other brands and drivers, the air often weighs heavy and acrid like a battle zone. It’s an intoxicating joy when your brand is winning, just as it can be brutally crushing when you lose.

Yet whether it’s an Arctic Cat racer who takes the victory, or another brand that gets the honors (like Todd Wolff here at the 1998 Warroad I-500 cross-country), Roger is always the FIRST person to shake their hand in congratulations.

This – more than his inventions, longevity, contributions and racing success – is why Roger has earned the greatest respect from his peers.